Context –

This is a continuing series on Trust in Society.

We previously told the story of Operation Trust to outline the core elements of trust in society. In this essay, we start with the fundamental question - why do you trust yourself?

Here's what to expect going forward –

Operation Trust: Debriefing the Collapse of Trust in Society

Axiom of the Mind: The Sense of Trust ← You are here

Lying Eyes: Believing is Seeing

Rhetorical Color: Signals and Emotional Shades

From Me to Us: Character

Friend Vs Foe: The Prospect of Trust

From Us to We: Communities of Myth

Status: Ability, Morality, and Culture

From We to Them: Culture Clash ← Writing Now

Fashion: Police Authority

Organizations: Brain of the Firm

Economic Geography: A Pattern Language

Let's Play a Game: The Map of Trust

“Knowing yourself is the beginning of all wisdom.”

- Aristotle Nicomachean Ethics

The most important thing to recognize about trust is that it is a sense, like your sense of smell, sight, or hearing. Unlike those external senses, trust is an emergent internal sense, like your sense of reason, fashion, or identity. While all of those senses might seem vastly disconnected from one another, they all operate under the same physical principles of perception.

To start it turns out Plato was right, you really are living in the cave of your own skull which we call a Markov Blanket, but even weirder, you are also the puppet master. You interpret the world through the stories you tell yourself and fit new information into those same stories in your head. No story is ever complete without the essential ingredient of character. Those shadows all have names, a history, and are the characters in our stories. But of course, you are the main character, the hero of our story. So what happens when your confident senses have to face the light of reality? When what was true is now false, and who was foe is now friend?

Those are the questions I am going to answer over the next few chapters. However to do that I have to begin at the lowest level of: how do your senses work, why do you trust them, and how does that lead to a trust in yourself? To do this I am going to explain Karl Friston’s Free Energy Principle of Perception (FEP). Although the primary purpose of Friston’s Theory is to explain how creatures perceive the external world through their sense, it’s deeper implications appear when you apply this idea internally.

The FEP is a little technical but it’s worth unpacking and thinking through, because it not only explains how your perceptions work, but how they can be wrong, how those perceptions become your identity, and why we need other people, whom we trust, to discover the truth.

But first a disclosure.

No One Really Knows

As neuroscientist Erick Hoel explained, our greatest limitation is that while neuroscienist, brain and nerve experts, have uncovered a lot about which areas of the brain do what and the networks of communications between those areas, we do not have a good theory for how it all fits together to 'make sense', sometimes called the Binding Problem.

Towards the end, of Pixar movie Ratatouille a hard-edged and severe critic of French food Anton Ego comes into the restaurant, where Remy (the rat chef) is working, to review their food. When the critic tries Remy's ratatouille, he is transported back in time to his mother's kitchen, he remembers the warm feelings that the dish brought him then, and again now.

This is the binding problem, and we have no definitive answer on how it works.

In other words, neuroscientists do not have an agreed-upon model, e.g., paradigm, for consciousness. This is an area of contentious debate, and while I am not a neuroscientist, there is one theory that lends itself well to exploring ideas around trust:

Karl Friston's Free Energy Principle of Perception.

Karl Friston is the most cited neurologist of all time, owing to his work on neural imaging. While Friston's work on imaging might be the backbone of modern neurology, his theories regarding the conscious mind are controversial, especially among philosophers but also among neurologists.

However, given that the theory is controversial, I present it as an assumption because the model is useful.

Axiom of Mind

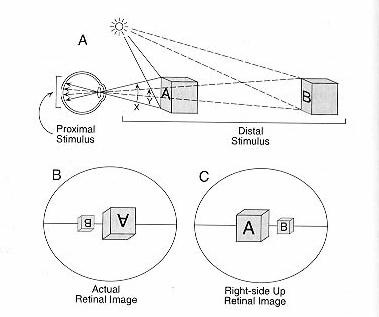

What does Friston's Theory say? Friston proposes that minds, meaning all sense-making creatures, function as a kind of prediction machine for the senses. In essence, your mind is constantly taking in low-bandwidth sensory inputs (vision, smell, touch, sound) and from that, your mind is constructing a high-definition view of the world around you. To take vision as an example, physically the human eye can only perceive a 2D image. The 3D world you experience is in reality the mind creating a 3-D world by making predictions.

And because your mind is actually making predictions based on past experiences, your mind can play tricks on you like the example below which asks How Many Objects Do You See? (Click for the Answer)

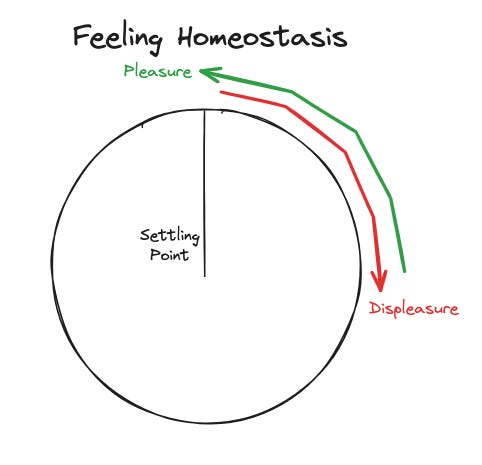

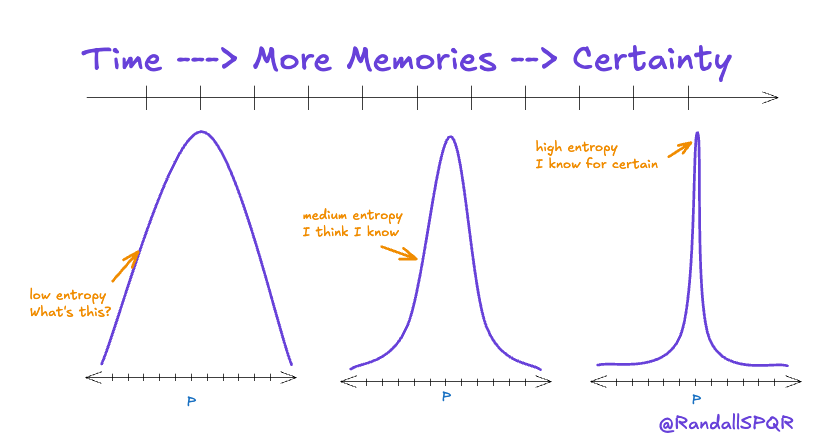

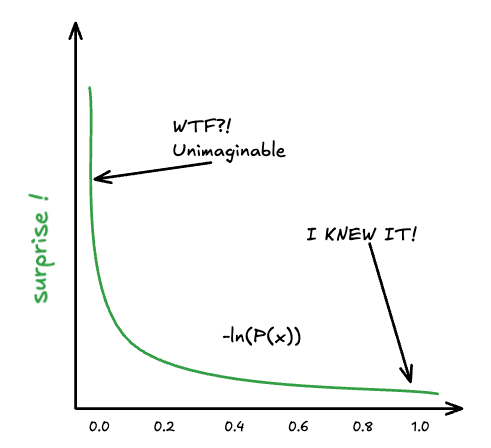

The phrase Friston uses for how brains function is 'self-evidencing with precision'. The key to the functioning of this mind is the Free Energy principle, or the 1st law of Thermodynamics, or entropy if you like. To be explicit, Friston says: 'Free energy is equal to the average internal energy minus entropy'. In the context of information, free energy means the expected probability of an event, and entropy is how much the expectation of the input and the actual input differ.

Formal: Free Energy = Expected Energy - Entropy

English: Surprise = Previous Expectation - Unexpected Reality

This is a simplified version of a complex idea, but it's important to understand the core intuitions before adding too many factors.

The scientific word for this is the homeostatic system. Homeostasis resists entropy or disorder; it seeks to find order in a chaotic world through predictions. Those predictions order the world by making it less surprising; it reduces the number of things to consider. Our senses require a lot of energy to operate, so it is most efficient to use them sparingly. The easiest way to do that is to ‘remember what happened last time' and only use the attention or the focus of our senses to fill in surprisingly new parts. But if our brains are constantly guessing to fill in gaps, how much of what we see and believe might be an illusion?

When everything is going according to your predictions and you feel nothing, that is homeostasis. However, when your predictions are wrong, that is when you notice something, and you feel either joy and happiness for the good stuff (found a $20 in your pocket) or fear and loathing for the bad stuff (ouch, that's still hot). Good things are by definition things that make our existence more predictable, reduce uncertainty, and resist entropy. Bad things make the world less predictable, and more chaotic.

So far so good, but if all of that is correct, then you get into the controversial parts of Friston’s Theory. To summarize:

1 - What we call consciousness is technical hallucination.

2 - Humans are not unique in this experience of consciousness.

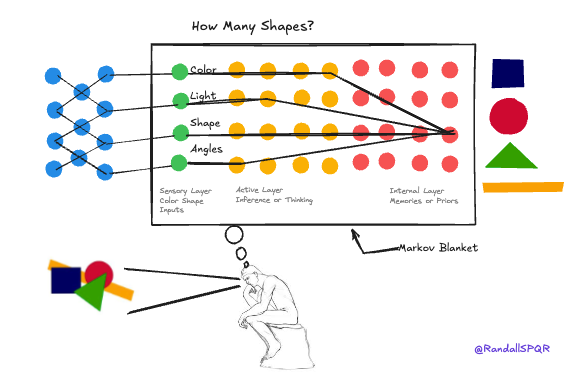

First, Friston argues that all sensory input passes through a Markov Blanket. It's a network of chained probabilities that take our current senses as inputs, compare those to what came before in the same context, and construct the world wholly within our own heads. This is what has led British Neuroscientist Anil Seth to say all experience is technically a controlled hallucination. In essence, your senses like smell, touch, hearing, and sight are electro/chemical signals to your brain, which your brain then compares to what it observed before, and it is in the combining of those things called active inference that you get consciousness. The important point is that we never directly observe anything; all of what we call reality is actively inferred in the brain. The Markov Blanket is the mechanism of combining our memories and senses to generate our conscious desires to seek out the good and avoid the bad surprises.

The best way to understand Markov Blanket is to see it as presented below. In this visualization, the left side in blue represents the external world like an image. The boundary you see is our Markov Blanket, which you can think of as our personal Platonic Cave. The green represent our senses, which interact with active states (orange), to compare them to the internal states (red) which are the past predictions we have about the world – think of these as memories. Friston's Law, which I will explain next, are the paths and explains how the green sensory inputs and the orange active thoughts work together to form and update our red internal predictions.

The Markov Blanket can be thought of as a semi-permeable membrane surrounding your mind. Imagine you're in a room where the windows are frosted glass. You can see light and movement outside, but not clear details. Your brain then uses what it already knows (past experiences) to guess what's causing those blurry shapes and changes in light. The frosted glass is like the Markov Blanket - it lets some information through, but your brain has to do a lot of guesswork to figure out what's really out there. This 'guesswork' is what Friston calls active inference, and it's happening all the time, mostly without you realizing it.

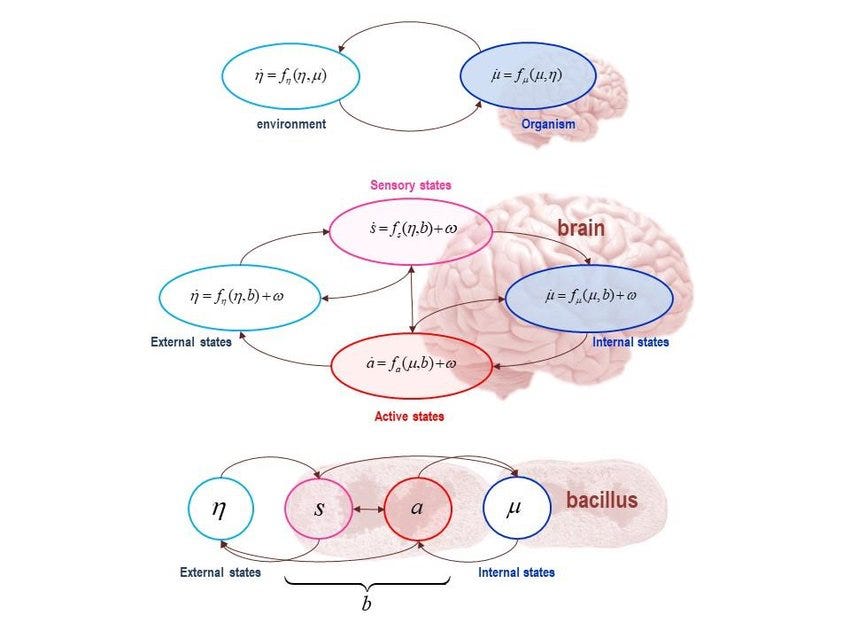

Second, because Friston's Theory of Consciousness is based on this Markov Blanket, it means that consciousness is not a uniquely human condition, but is rather something that exists at all levels of life. This makes sense to me; my dog is certainly conscious, and lots of research on ravens, crows, and octopi would suggest that they too are conscious. However, taken literally, a Markov Blanket also describes a plant or a bacterium as well. Much of the proof for Friston's Theory actually comes from the ways that very simple organisms, called cellular automata, can create vastly more complicated structures through a kind of self-assembly by following the equations that make up the Markov Blanket.

Specifically, Friston's Theory is this diagram where the first image shows the classical view of direct observation feeding straight into the brain. Second, shows the active and sensory states that together make up the Markov Blanket separating our minds from the world of our senses. Third is the simplest form of a Markov Blanket, where a bacterium has a single primitive sense of smell.

If this diagram looks intimidating, let me explain in plain English, most of what you perceive in the world is in fact a memory. The more times you have seen or sensed something, the more certain you are of that perception, so you only give attention to something surprisingly out of place, and only to the degree that your past certainty allows you to update. No matter how convincing a piece of evidence is to our senses, we rarely fully update our thoughts; we are all anchored to our past perceptions and our certainty of those perceptions on a fundamental level.

That is why we say Self-Evidencing with Precision.

Since we are self-evidencing with precision, you can see the seeds of our well-known mental biases. Like Availability Bias, the bias to only consider known explanations, Status Quo Bias, the bias to prefer things as they are over the uncertain promise of something new, and Confirmation Bias, the bias to agree and accept new information that confirms our pre-existing beliefs. Or why do people become more confident and then nostalgic with age?

Formally, Friston's Markov Blanket is a type of Bayesian updating, so we get one-half of the internal expectation (memory) times its precision weight (certainty) times the active (current sense) state minus the log of the initial precision weight (ambiguity).

Therefore:

Formal: Free Energy = Average Energy - Entropy

Where n is the external senses, and u is the past sense states

Free Energy = u - n

Friston's Law: Change in Free Energy = 1/2 (E * W * E - log (W))

Friston’s Theory was developed to explain how creatures perceive the external world through their sense, but when we turn it inside and reflect a new pattern emerges.

Not Out But In

David Egelman has said “Our perceptions are a hallucination that is anchored by external input from our senses.” If we create the words in our heads based on the tiny silver of the world that our senses are attuned to provide, but what they are is entirely an interpretation of our own making. What happens to that hallucination and interpretation when it is not anchored to external inputs but feeds back on its own internal inputs?

Life is a movie that we watch inside our heads, and our self, our identity is the character we choose to play. Often this is the source of our inner monologue. Neuroscientist Markl Gazzineza calls this the “The Interpreter Module” it’s job is to create a storyline and narration for our lives, it generates explanations about our perceptions, memories and actions and the relationships among them. What Friston’s Theory implies is that when we reflect internally, we are self-evidencing by using our past memories to explain why we are thinking something today.

This leads to a personal narrative that ties all the disparate aspects of our experiences into a coherent whole.This personal story is almost certainly wrong, since its job is to reorder things so they fit our preexisting notions. Typically it makes us believe that we are all better on average than everyone else. We are more moral, virtuous, better drivers, and smarter than those around us, and we have all the evidence we need conveniently tucked in our heads.

It even makes us think we are better today than yesterday. In a study, a group of college kids was asked to self-report how they saw themselves across a range of personal traits. Six weeks later, everyone was asked to come back, but this time the researchers showed the average ratings of all the other people. As you might have guessed everyone then re-ranked themselves to be just above average. Except it was not the group average, it was their own scores from 6 weeks earlier! The students were now saying that they were more honest, vitrious, and moral than they were saying 6 weeks prior.

The lesson is that we are all running an operation that helps us make sense of fuzzy sensory inputs, which also gives a false sense of overconfidence in those senses. When we turn that operation internally, it leads to a sense of Personal Superiority that is a persistent feature of all people, regardless of how good and moral or cruel and horrid they may actually behave. What memories do you rely on to define who you are? Are you confident they are accurate, or could they be self-reinforcing stories?

The Ubermensch and the Benefits of Friends

The reason for this over-confidence is that for a homostatic system to stay in balance, it needs to fuel and feed itself continuously. While this location might be great with lots of food, over time, that food resource gets exploited to exhaustion. Living systems must continue to explore new resources. This is commonly called the explore/exploit tradeoff. Trees will cast their seeds into the wind, bees will fly off in random directions, and humans will sail the seven seas in the uncertain hope of finding a new place with good resources. All three do this even though the odds of success for any individual seed, bee, or journey are slim. They do this because those rare successes have rewards that exceed what any individual could consume and therefore the whole group benefits. While the first tree is often the tallest, and the first bee gets the most pollen its the next set of trees, and the next bees who consume the majority of the newly found resource.

Nature is a dangerous place and fear is the logical reaction, but it’s also a path to extinction. The species that have survived have a slight over-confidence that we might call curiosity. Individually, this is suboptimal; curiosity kills a lot of individuals. But for the group to survive this over-confident sense of curiosity is needed and optimal.

Therefore, in isolation, a person is more likely to be too trusting of themselves, they believe in their bullshit; overconfidence is the error we make and the problem we need other people to correct. For example, I might think the next valley is full of ripe bananas, and I would start walking over based on that belief. However, if another person, Bob, just came from there and told me the bananas were gone, he could save me the trip. An isolated mind in a social situation is known as a cynic; the cynic would assume that Bob is lying to selfishly keep those bananas for himself, “I trust myself.”

The opposite of cynicism is not naivety but rather skepticism. How sure am I of those bananas, and if there were still more bananas over there, why is Bob here now?

Because a skeptic doubts even themselves. And this is as true of the external world as it is of our internal worlds. The skeptic will use a sense of reason, but as Hugo Mercier put it:

"We produce reasons in order to justify our thoughts and actions to others and to produce arguments to convince others to think and act as we suggest. We also use reason to evaluate not so much our own thought as the reasons others produce to justify themselves or to convince us.”

This means reason does not work in isolation, it only works when it is checked against and agreed upon by others who have different self-evidenceing reasons and are, therefore, skeptical of you. Our sense of reason is a way to socially correct our individual overconfidence senses. You live inside your head, and you can not read the label from inside the jar, but others can.

An Exercise for the Reader

I am asking you my dear reader to be my fellow skeptics, and I invite you all to tell me how and why I am wrong. Although my stories and explanations are fully believable to me, for a story to be considered real, it has to be a story that we all share and believe.

Reason only works in a community.

In the end, the sense of trust we place in ourselves is as much a construction as any other part of our perception. We navigate a world filtered through our Markov Blankets, guided by memories and personal narratives that reinforce who we think we are. As Feynman said, “The first rule is not to fool yourself, and you are the easiest one to fool.” In the world of science, we have agreed upon rules for what counts as objective evidence, but it gets much trickier when are are depending on our senses. In the next section, we will look at a few examples where you can not see the truth unless you already believe it.

You will not believe your Lying Eyes.